By Bipul Chatterjee and Surendar Singh

The mega regionals may prevent developing countries like India from penetrating the global value chains

The dominant feature of international trade in the 21st century is the emergence of global value chains (GVCs). The sharp rise of trade through GVCs is changing the pattern of cross-border trade. As a result, GVCs are an important driver for productivity, employment and competitiveness of a country’s production system. It is estimated that as much as 60 per cent of world trade in goods is occurring through GVCs. From ‘trade in goods,’ we have entered into an era of ‘trade in tasks’.

‘Trade in tasks’ is transforming cross-border trade in two ways. First, GVCs have increased the importance of imports in domestic production as well as exports as the contribution of intermediate imports is almost one-third of total value of global exports. Since 1990s, it has doubled. Secondly, over the last decade service sectors have emerged as integral part of global value chains. Domestic production and exports of goods are much more embodied with domestic and imported services.

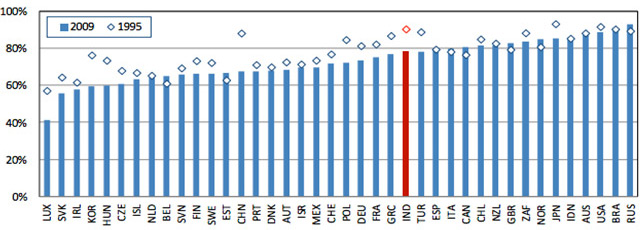

While taking a close look at the data on value added contentof gross exports in recent years one can observe this trend. For instance, India’s domestic value added content of exports was 78 per cent in 2009, 12 percentage points lower than that in 1995, illustrating an increasing fragmentation of production and greater integration into global value chains (Below).

Source: www.oecd.org/sti/ind/TiVA_INDIA_MAY_2013.pdf,page

As per the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, the share of foreign content in India’s exports is increasing in all sectors except agriculture. In 2009, it was nearly 50 per cent in case of ‘other manufacturing industry’, a four-fold increase since 1995. The foreign content of ‘business services’ also increased significantly: from three per cent to 14 per cent, reflecting an increasing importance of services embodied in trade in goods.

Therefore, and contrary to popular perception, it is not true that India has missed the bus of entering into the global value chains. More importantly, a careful look at Figure 1 reveals that countries like China, Japan, South Korea and many European countries are fast integrating into global valued chains. Therefore, it is an imperative for India to have preferential trade agreements with them and India’s new generation bilateral trade agreements are to be looked at accordingly.

India has comprehensive economic cooperation agreements with Japan and South Korea. It is negotiating a free trade agreement with Canada, the 28-member European Union and the group of European Free Trade Area countries. Among other major trading partners, Australia and China are part of the negotiations for a Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnershipagreement of Asia and the Pacific.

The question is whether India will be able to maintain this momentum or not. It is in this context, the emergence of mega regional trade agreements such asthe Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), the EU-ASEAN free trade agreement, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) of Asia and the Pacific are to be looked at. They will reinforce ‘trade in tasks’ along with further embodiment of services into goods trade.

It is expected that these mega regionalswill end up with a gold standard on trade, means a much higher level of rules and regulations on stricter rules of origin, sanitary and phyto-sanitary measures for consumer safety, technical standards such as packaging and labeling, intellectual property rights for addressing trade in counterfeit goods, data security, etc. They will also cover new issues such as electronic commerce, trade-related exchange rate management.

These mega regionals may prevent developing countries like India from penetrating the global value chains; thus, posing a serious problem to their right to trade as well as employment generation through trade. Either they are not part of these mega regionals or they lack domestic capacity to adhere to such a high standard of doing trade. As India is part of the RCEP negotiations, it is important to understand how India negotiates this mega regional so that it does not lose much of its market access in the West as well in those countries in the Pacific who are part of the TPP negotiations.

This is because not only that Trans-Pacific Partnership, Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnershipand EU-ASEAN FTA will have negative impacts on India’s employment-intensive sectors such as textiles and clothing, agro-processing, automobiles, but also there will be negative impact on inward foreign direct investment to India, which will have cascading implications on our manufacturing and services.

Therefore, the issue is not whether India joins the Trans-Pacific Partnership or not as that is not possible. It is about how India should enhance its domestic standards, intellectual property rights and other trade-related regimes and effectively negotiate them and other new issues at the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership of Asia and the Pacific.

As RCEP has many common members with TPP, it is expected that they will insist to have TPP standards in common issues to be covered in RCEP as otherwise they will not have any incentive to adhere to expectedly higher TPP standards. Indian negotiators will face this challenge while negotiating the RCEP agreement.

Fortunately, RCEP is still at a formative stage. However and instead of arguing that RCEP should agree to trade-related rules and regulations somewhere between India’s domestic regimes and expectedly higher TPP standards, India should negotiate a built-in agenda to converge RCEP’s rules and regulations with those of TPP.

For that to happen and India to enhance its trade competitiveness, there is an urgent requirement of amendingour trade-related laws such as the Bureau of Indian Standards Act and apply non-discriminatory national treatment principle to imports as well as domestic production. This requires the strengthening of the capacity of our trade-related bodies for effective implementation of modern laws.

Authored by Bipul Chatterjee, Deputy Executive Director, CUTS International (bc@cuts.org ) and Surendar Singh, CUTS International (sus@cuts.org )