Unctad as a forum seems to have adopted Mr

Raul Prebisch’s basic idea of critical enquiry

through its own analytical research.

By Pradeep S Mehta

Having attended the past four triennial meetings of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (Unctad), this writer has been witness to the UN body’s struggle to maintain its critical role amidst pockets of opposition.

It is much more than being a standing conference, which only means it meets often and does little more than that. Because of its bureaucratic and democratic nature, people have also dubbed it: Under No Circumstances Take Any Decision.

Humour apart, Unctad is not mandated to negotiate any agreement and, hence, decision-making is relegated to, often hectic, negotiations on the text of its declaration. However, some agreements such as those on commodities have been negotiated under its banner. That said, the declarations, unlike the ones adopted by the WTO ministerials, do have a bearing on the international community’s approach to the complex issues of global trade policy, where all countries are at different levels of development.

This is not a simple task. Therefore, given the magnitude of the problems facing developing countries in international trade and the need to address them, the conference was institutionalised to meet every four years to address the above concerns.

Economic order

Traditionally, Unctad had been conducting discourses on the ‘new international economic order’ (NIEO) and has been making its case on the basis of analytical policy-oriented research, at least until the debate on NIEO was replaced by the Washington Consensus.

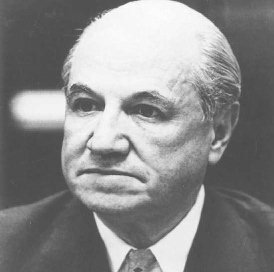

Such an approach has been inspired by the teachings and vision of Unctad’s founding Secretary-General, Mr Raúl Prebisch — the prominent Argentinean economist and thinker with a strong influence on world economic debates — who served Unctad from 1964 to 1966 and advocated preferential access to the markets of rich countries and regional integration.

During the Unctad XI, 2004, held at Sao Paulo, Mr Rubens Ricupero, the then Secretary-General, while delivering the 12th Raúl Prebisch Lecture reminded the audience about Mr Prebisch’s legacy of ethical commitment to genuine development.

The ideas were originally developed in the late 1940s or early 1950s. One instance is the ‘recognition of technical progress as a key to the development process, or the need to redress the asymmetries in trade between the centre and the periphery, which also results in a terms-of-trade bias against developing countries.

This, and the adoption of industrialisation policies to correct that bias, the prescription of not only an import substitution strategy but also of export promotion of manufactures as the best recipe for reducing the trade gap, are some of the issues that still occupy centre-stage in the current discourse. Research and investigation in this area, according to Mr Ricupero, has been adopting a ‘systematic critical inquiry method that has become inseparable from the modern approach to the social sciences’.

Change in approach

With Mr Ricupero asserting the relevance of Mr Prebisch’s core thinking, even in today’s economic set-up at the eleventh ministerial meeting of the Unctad and the Raúl Prebisch Lecture remaining an essential ritual at Unctad since its inception, it seemed that the Unctad was following a certain approach to investigating problems relating to trade and development.

However, the twelfth ministerial meeting of the Unctad in Accra, Ghana during April 20-25, 2008 made an exception, with no Raúl Prebisch Lecture being delivered.

So far, so good. The Unctad is upholding the essence and relevance of its foundation. In the1960s and 1970s, with its profound work on GSP (Generalised System of Preferences, 1968) wherein rich countries provide market access to exports from developing countries; its facilitation of commodity price stabilisation, particularly of exportables relevant to developing countries; its role in providing development aid, and its evolving work on trade and competition policies, Unctad has been advancing a global economic reform strategy.

The 1980s and 1990s at Unctad witnessed the challenge of a changing economic and political environment. Development strategies became more market-oriented, and the ‘one-size-fits-all’ type structural adjustment programmes by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund dragged many developing countries into severe financial crises and economic stagnation. Unctad highlighted the need for a differentiated approach to the problems of developing countries to address the development agenda in a globalising world.

More recently, Unctad’s work on FDI (foreign direct investment) has become a major component of globalisation based on its extended analytical research effort on the linkages between trade, investment, technology and enterprise development.

‘Failed’ ideas

All such broad-based activities of the Unctad are in keeping with the words of Mr Prebisch, “to renew our ideas is an imperative,” spoken before his death in 1986 in one of his last lectures in Medellin, Colombia. Even so, his ideas have been subject to much criticism. His followers affirm, though, that much of this is based on distortions of his work rather than his original contributions. It would be wrong to look at Mr Prebisch’s proposals ‘out of their historical context’, they say.

It should be taken into consideration that ‘many of his proposals were made in the light of the Great Depression, and the collapse of the international trade and financial system in the 1930s, whose reconstruction had barely begun when he published his works (Prebisch, 1949, 1951, and 1952). Even in India, Mr Prebisch’s works are commonly labelled as failed prescriptions for India’s growth strategy. Nonetheless, the noted trade economist, Prof Jagdish Bhagwati, while commenting on Mr Prebisch’s essay, once described him as a remarkable economist.

Poor implementation

Properly understood, the lessons of the Singer-Prebisch thesis, which provided a justification for import substitution industrialising (ISI) policies were not properly implemented by governments. Whether the supposed import substitution policy of the 1960s in India can be considered as leading to a predominantly socialist-type planned economy, with ‘excessive’ state intervention is debatable. In this context, another well-known trade economist and Prof Bhagwati’s acolyte, Prof Arvind Panagariya, assessing India’s post-Independence economic history in his new book, has blamed extreme government intervention culminating in restrictive policies on investment, and not Mr Prebisch’s prescriptions, for damaging India’s growth effort.

Such an omission can be explained by Korea’s noteworthy experience in this regard — it practised import-substituting industrialisation for two decades before shifting towards an export-led growth policy. Arguably, today’s prescribed export-led growth strategy is working well for a handful of countries. So, it may be said that no set formula can be prescribed to ensure economic growth.

Current relevance

Unctad as a forum seems to have adopted Mr Prebisch’s basic idea of critical enquiry through its own analytical research. The attitude of readiness to change and innovate to suit the need for development and poverty alleviation reflects its credo. Consider, for instance, one of Mr Prebisch’s reformulated ideas in the context of the current global food crisis.

Food self-sufficiency appears to have regained some relevance, as against many who thought on the Ricardian lines of comparative advantage. In the case of most poor African countries, 60-70 percent of their foreign exchange is used to import food, leaving very little for importing intermediate manufacturing capital goods for progressive industrialisation. The current development policy-based literature is increasingly found to be advocating import substitution in African agriculture.

Though the Unctad XII did not organise a ‘Raúl Prebisch Lecture’ this year for some reason, by no means was it a sign of rejection of Mr Prebisch’s critical development thinking. The issues taken up for discussion at the last conference at Accra in April, 2008, followed by the Accra Declaration, are indeed proof of this.

The author is Secretary General, CUTS International, a leading research, advocacy and networking group and can be reached at psm@cuts.org